If you have an annual income of 32,400 USD or more per year, you belong to an exclusive club of the richest 1% in the world. This might sound absurd to those new to the concept of global income inequality, but is perhaps a bit more palatable when we realise that a third of the world lives on 10 dollars a day (that's 3,650 USD a year).

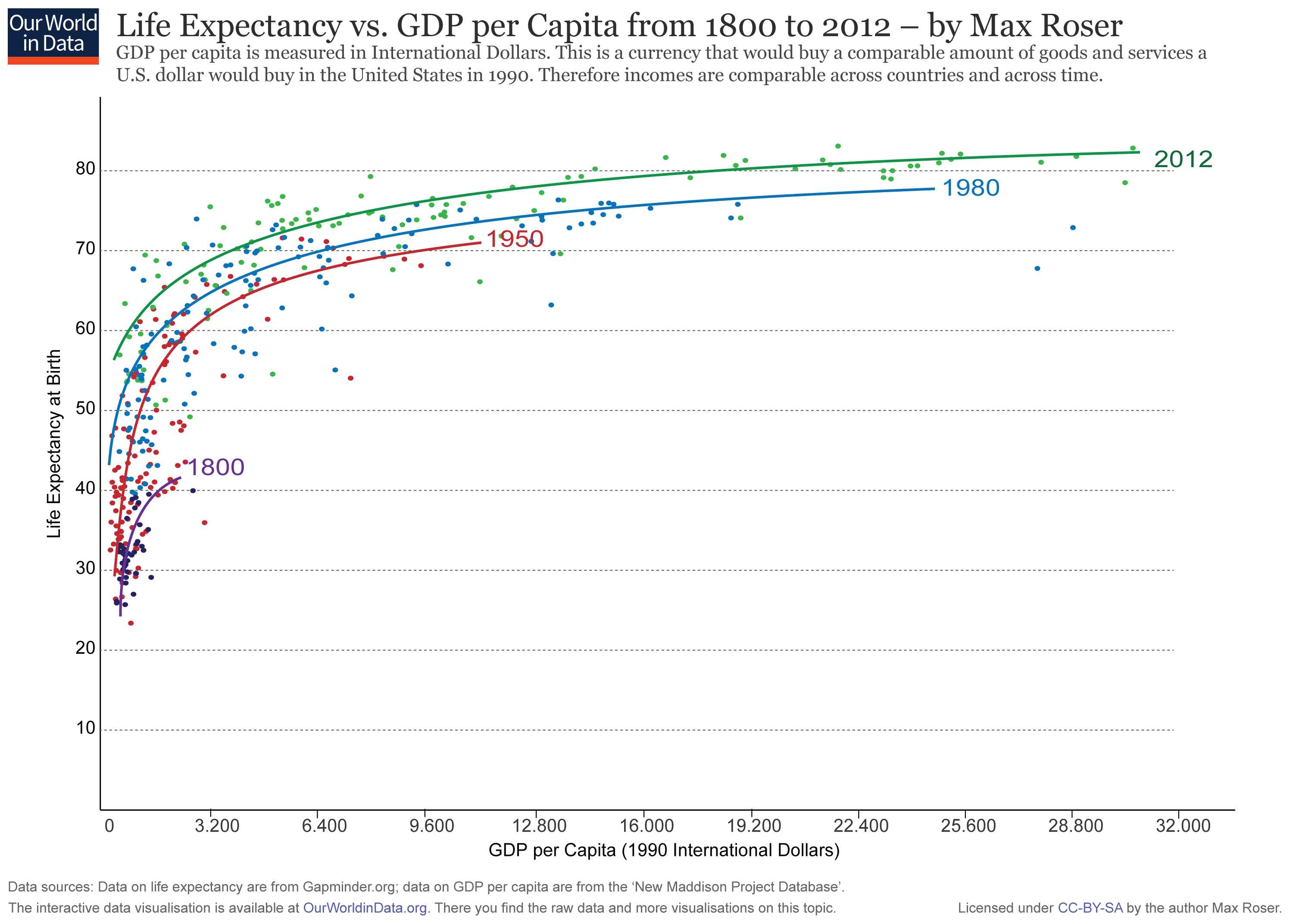

A common response to hearing this is that it can be explained through cheaper goods in poor countries, exchange rates, or that poor people can produce a lot of their goods and don't need as much currency. However, it is possible to account for purchasing power parity and the economic value of self-produced goods. Fact check after fact check confirms this - if you are reading this article from a first-world country, you are likely in the 1%. If you are still incredulous that people can survive on so little money, the answer is that they don't. The global poor experience malnutrition, limited water, little or no electricity, lack healthcare, and end up dying up to 30 years earlier than the rich as a result.

What responsibilities should the 1% have? We know that there are global issues facing the 99% less fortunate. However, as we surround ourselves with those equally rich or richer than us, we feel overwhelmingly average.

As mere individuals, the scale and complexity of these problems are hard to comprehend. Often, we choose to simply ignore them, chasing the smaller personal goals we have set in our individual rat races, like buying a house or raising kids. We hope that there is someone else, someone smarter, richer, and more influential, who will solve the problems for us. Is there a practical way to both live our lives and do good in the world?

In my search for answers, I have come across concepts which I have distilled into my own practical solution described in this article. I hope it may help spark debate, and for others to improve on what I have discovered so far.

Global problems: which should we address?

Global poverty, climate change, the superbug, and AI misuse are a small sample of the biggest issues facing humanity. But there's not much use in solving global poverty if the Earth stops being able to sustain life. In the long-term, in addition to tackling human-specific problems, there is a more fundamental issue that all other initiatives need to comply with.

Simply put, the Earth produces a fixed amount of resources annually that we can work with, called biocapacity. In the same way that overdrawing funds from the bank results in a financial crisis, we need to ensure that we don't overdraw the Earth's capacity to sustain life while solving problems. To do this, we need to determine our environmental budget.

In Sydney, Australia, I am surrounded by convenience. I have electricity, water, and waste management. I am surrounded by shops, restaurants, roads, parks, and schools. I am also surrounded by lots of other people, each enjoying the same convenience as me. What I don't see is the infrastructure required to provide this convenience, and which fraction of that infrastructure is solely dedicated towards my lifestyle.

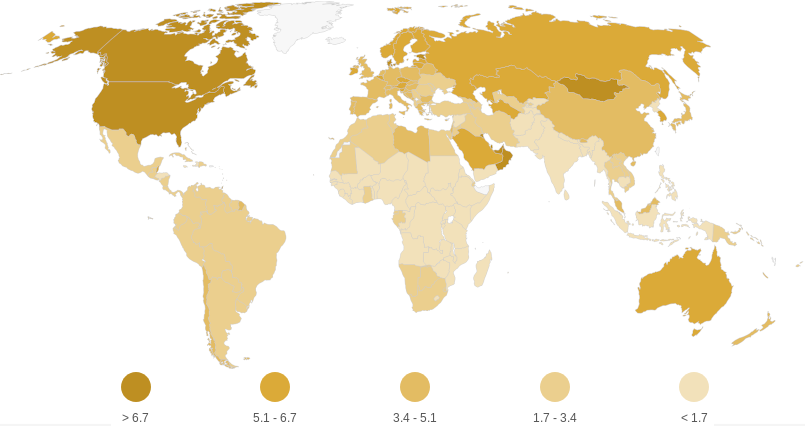

The Global Footprint Network figures that the average person in Australia requires 6.6 global hectares of productive resources (in 2016). The unit of a global hectare is a little difficult to explain, but I can loosely approximate it as a regular hectare. This means that somewhere out there, there are 9-10 FIFA football fields of infrastructure, producing the water, food, clothes, construction material for my house, electronics for my computer, and so on, dedicated just for me.

The good news is that Australia is a big country. Australia as a country can naturally regenerate 12.3 global hectares worth of resources per person per year. This means that Australia can let all of its residents happily live at this level of consumption, and each person in Australia has 5.7gha of surplus left to share with the kangaroos, koalas, and thousands of other species that also live in Australia. It sounds a little selfish to take half the area just for humans, but it's certainly better than nothing.

However, not every country is as large or lucky as Australia, and not every country is as sparsely populated as Australia. Globally, we overdraw the Earth's resources, with humans consuming the equivalent to 1.7 Earths biocapacity. Earth may currently have enough stock to allow for this, but not all stock is equal, and efforts required to tap into this stock are at the expense of others species.

The extrapolation of this form of excessive consumption is mass extinction. Ethically, it's probably a good idea to avoid this. Unfortunately, the extinction process has already started. WWF estimates extinction rates that are 1,000 to 10,000 times higher than the background extinction rate (i.e. the rate if humans weren't around).

Regardless of any large issue we choose to tackle, our strategy needs to also be such that our ecological footprint does not exceed the biocapacity available. Can we balance our ecological budget and do good at the same time?

Net-positive living is the solution to biocapacity overdrafting

Architects are no strangers to minimising ecological footprint, otherwise known as sustainable design. When architects design buildings, the good ones usually consider strategies to minimise unnecessary resources, be it electricity, water, or construction material. Some architects go further and try to design buildings that produce ecological resources. This is a concept called net-positive, or regenerative architecture.

Net-positive buildings are designed as a species within an ecosystem. These buildings, like all species, consume resources, but most importantly, produce resources that benefit other species. This is similar to how biological species work in natural ecosystems. These relationships are important, as the more interdependent species are, the more resilient an ecosystem is against the risk of collapse.

The good news is that we have managed to design net-positive buildings with a ledger of their biological impacts over their lifespan. Where they take from the environment, a strategy is in place to give back more than they took. There are buildings that sequester more carbon than they output, or improve water quality, or improve soil fertility, or reduce ecological dead-ends, or provide habitat. So if we can design buildings to be net-positive, can we design our lifestyles to be net-positive too?

In the case of humans, we consume a lot. Minimising our consumption (and limiting population growth) are valid and extremely effective strategies. However, in this article I want to talk about what we produce, which is a trickier problem. Things we produce have an abnormally large negative contribution to the ecosystem. As an example, our production of plastic is a bit of an ecological dead-end, as it doesn't create useful nutrients that new life can spring from. In fact, our plastic tends to almost universally harm other species.

As you're probably aware, it is quite hard to avoid plastic. Indeed, plastic is just one of many problems that are built into our lifestyles and urban infrastructure. The very act of commuting to work produces air pollution and burns carbon. Eating a meal contributes towards unethical farming practices and drinking water adds just that bit more to the unsustainable extraction of freshwater.

There are "extreme" lifestyle changes that have been demonstrated to mitigate these issues. Such examples are urban permaculture, veganism, the zero-waste movement, and not having children. They require a level of discipline and dedication that may be simply unlikely for lots of people. It also requires a lot of research about things we aren't trained in or access to things we don't have. For instance, if I live in a 1 bedroom apartment with no garden, my options for planting trees to offset my carbon footprint are limited. Or perhaps we want to help with the issue of water scarcity, but we have no idea what we can even do.

To start with, I've identified the following major categories of human consumption and production. There are probably more, but it's a start:

- Carbon footprint

- Ethical food consumption

- Sustainable water usage

- Biodiversity and loss of ecosystems

- Waste management

- Air pollution and quality

I'm not an expert on any of these topics. They're all big issues, but try as I might to avoid plastic, take the train, or buy free-range eggs, what impact can I really have?

What if we could pay others who are trained and actively involved to solve the problems for us? It might sound like a cop-out, but if the alternative is doing nothing, what could we achieve with purely our wallets? How do we find these people? How do we guarantee that they can make a difference? If we make 32,400 USD a year as the richest 1% of the world, is 1,620 dollars a year, 135 dollars a month, or 5% of our salary enough to live a net-positive life?

It might sound crazy, but it might just be possible. Let me explain how.

Effective altruism allows specialists to do what they do best

Effective altruism is the concept that not all altruistic efforts are equal. The example given by Peter Singer in his TED talk is that if you were interested in helping blind people, one option is to sponsor a guide dog. The total cost of training a guide dog and its client comes out to above 40,000USD. However, there are blind people in developing countries which can have treatments that only amount to 25USD per treatment, thanks to the preventability of the affliction, and the magic of exchange rates. Therefore, a utilitarian approach would suggest that a charity dealing with the latter would be 1,000 times more cost-effective than raising guide dogs.

As a stellar example, the Against Malaria Foundation recommended by GiveWell has a return of protecting 90 people from malaria for 3-4 years for every 100USD donated. If you donated 5% of your 32,400USD yearly income, you would protect 1,450 people from malaria every year. In contrast, if you quit your job and became a doctor, you would only save about 20 lives over a 43-year career. This doesn't mean that doctors aren't good to the world, on the contrary: doctors are what makes health improvement even possible. It also doesn't mean that doctors should quit their jobs: that would be the wrong conclusion. What it does demonstrate is that a focused financial redirection can have a large impact, even if you aren't employed in the industry.

By identifying effective initiatives that others are taking to solve global problems, can we support them financially to "offset" the negative aspects of our own lives? To answer this, we will need three things:

- An account of our own ecological footprint

- An initiative which makes the world a better place with measurable impacts

- A dollar value to offset our actions

I will give examples from my own life below, using the categories of human consumption and production identified above.

Example ecological footprint calculations

Carbon footprint

The concept of a carbon footprint has been heavily researched. This makes it easy to calculate my personal carbon footprint, easy to identify initiatives that help store carbon, and easy to place a dollar value.

We tend to emit carbon directly through our transport, and indirectly through our lifestyles. These are easily calculated using online carbon calculators such as this one from ClimateCare.org and this one from CarbonFootprint.com.

Carbon from electricity usage is included in my electricity bill. I actually pay more for green energy (note: renewables still have a carbon footprint, just less so!), but in the figures below I have pretended that I do not purchase green energy.

Car travel can be derived by looking at my car maintenance logbook and the odometer readings. Based on data from 43 vehicles, 1,329 fuel-ups and 351,879 miles of driving, the 2006 Honda Jazz gets a combined average MPG of 33.63 with a 0.50 MPG margin of error. Feel free to look up your car.

Train and bus travel is easy to calculate by measuring a map. You can do this for free using Google Maps online, although if you are capable I would encourage doing this exercise with open-source software such as QGIS and OpenStreetMaps.

Here are my personal results for the first six months of 2019:

- Jan 2019: 7.59 tCO2eq

- 236kWh of electricity: 0.21 tCO2eq

- 730km of car travel: 0.13 tCO2eq

- 716km of train travel: 0.03 tCO2eq

- 3km of bus travel: negligible

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 7.21 tCO2eq

- Feb 2019: 8.74 tCO2eq

- 207kWh of electricity: 0.18 tCO2eq

- 659km of car travel: 0.12 tCO2eq

- 845km of train travel: 0.04 tCO2eq

- 15km of bus travel: negligible

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 8.40 tCO2eq

- March 2019: 7.43 tCO2eq

- 229kWh of electricity: 0.20 tCO2eq

- 730km of car travel: 0.13 tCO2eq

- 803km of train travel: 0.04 tCO2eq

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 7.06 tCO2eq

- April 2019: 9.14 tCO2eq

- Flight from Sydney (SYD) to Kuala Lumpur (KUL) via Singapore (SIN) (return): 1.85 tCO2eq

- 222kWh of electricity: 0.19 tCO2eq

- 706km of car travel: 0.13 tCO2eq

- 281km of train travel: 0.01 tCO2eq

- 5km of bus travel: negligible

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 6.96 tCO2eq

- May 2019: 9.62 tCO2eq

- (Forecasted) 229kWh of electricity: 0.20 tCO2eq

- 730km of car travel: 0.13 tCO2eq

- 779km of train travel: 0.03 tCO2eq

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 9.26 tCO2eq

- June 2019: 7.8 tCO2eq

- (Forecasted) 222kWh of electricity: 0.19 tCO2eq

- 706km of car travel: 0.13 tCO2eq

- 834km of train travel: 0.04 tCO2eq

- 1500-2000USD of secondary emissions: 7.44 tCO2eq

This gives an average of ~8.4 tonnes of CO2 per month. I personally find it interesting how much higher secondary emissions are compared to primary emissions.

Charity evaluators have heavily researched carbon initiatives. One of the most cost-effective charities in the field is the Cool Earth initiative. If the Cool Earth charity is able to reduce CO2 emissions by 0.38 USD per tCO2eq, it will cost me only 39USD per year (or 3 dollars 20 cents per month) to become net-zero in terms of carbon. Even if I conservatively took the upper bound of the research estimate at 0.71 USD per tCO2eq, it only comes out to be roughly 6USD a month. This is very affordable.

I'm in Australia, so if I donate 20AUD a month (the cost of a dinner at a nice restaurant), this is equivalent to reducing all my CO2 emissions 2-4 times. This should be enough to cover any inaccuracies in my estimations, and still have an additional net-positive impact.

For interested readers, there is some criticism of Cool Earth, as well as suggestions to look at other approaches such as initiatives around contraception.

Result: ~14USD per month

Ethical food consumption

Our food systems have an animal cruelty problem. We've covered the carbon aspect of our eating, and later we'll cover the water use and loss of biodiversity, but we need to do something about our actual treatment of animals.

The average Australian in 2017 eats 8.6kg of sheep, 21.1kg of beef, 21.3kg of pork, and 44kg of poultry every year. Let's round that up to 100kg of meat carcass per year. Note that our actual consumption weight would be slightly less, as carcass includes disposable parts such as bones, food prep, and spoilage.

Charities that deal with animal cruelty are researched to a lesser quality compared to human charities or environmental charities. Simply put, it's harder to measure the quality of life changes with farming practices, and even harder to confidently attribute these changes to the actions of a charity.

That said, Animal Charity Evaluators, the animal-focused equivalent of GiveWell mentioned above recommends the Albert Schweitzer Foundation. Here's the claim from the website.

From an average $1,000 donation, ASF would spend about $530 on corporate outreach campaigns. They would spend about $270 on individual outreach, $160 on legal advocacy, and $40 on media outreach. Our rough estimate is that these activities combined would spare -110,000 to 220,000 animals from life in industrial agriculture.

The negative values are because it is quite hard to actually guarantee that the charity itself is doing good instead of harm. The detailed review additionally warns that these cost-effectiveness estimates should not be taken as an overall opinion of the charity, as they are very broad approximations. In fact, they encourage a low degree of confidence in these numbers. If you wanted to truly select an animal cruelty charity to support, it is recommended to read the full qualitative analysis. If you did want to focus on quantitative analysis, there are ethical food calculators online.

That said, using the numbers as a ballpark is better than nothing. If we simplistically take the midpoint of the 90% Subjective Confidence Interval, it results in about 55 animals spared per dollar. It doesn't specify exactly what type of animal it is (but the report suggests that it is not fish), so we can be conservative and imagine that they are the smallest common animal out there: chickens.

If we further continued our overestimated ballpark that we ate 100kg of meat per year, this is equivalent to 800 125g drumsticks, or affecting the lives of 400 chickens. Obviously, we eat more parts of a chicken than just the drumsticks, and we also eat other types of meat, but chicken drumsticks seem to be the lightest quantum of meat we can use to conservatively maximise our animal count. Even with this inflated number of animals, it still only costs 8USD a year to offset our actions. We could happily multiply that by a factor of 10 as a penalty for the ultra rough calculations we're doing, and the resultant of 80USD per year is still within our budget.

Result: ~7USD per month

Sustainable water usage

Water, like carbon, is relatively easy to calculate. Apart from looking at your water bill which has your direct water consumption, there are some indirect water usages through our lifestyles, such as eating meat. I found a water calculator from WaterFootprint.org and WaterCalculator.org.

My water usage is not metered separately from my landlord, so my water bill is not an accurate representation of my direct consumption. However, I have conservatively outlined the following lavish lifestyle:

- 2x10 minute showers per day with a standard showerhead

- 1.5 laundry loads per week

- 1x10 minute dishwashing session

- 1x5 minute garden watering per week

- No car washing

This comes out to 12kL per month. To put this into perspective, 10 litres a day is seen as a threshold where people become water refugees. The Sphere Handbook (page 107) says that the basic water requirements to be used for planning refugee camps ranges from 7.5-15 litres per day. Therefore, my water consumption can serve 26 to 53 refugees.

A Guardian article about the drought in Indian villages describes residents who are too poor to buy water due to water scarcity. Those who can afford water need to pay 4USD per 1,000 litres. If 4USD per person sounds affordable to prevent a water refugee crisis, it means that we can certainly make a big impact.

But let's take a look at our indirect water consumption. Here's a conservative estimate of what I eat:

- 125g of meat per meal

- 4.5kg of cereal products per week

- 2kg of meat per week

- 2kg of dairy per week

- 8 eggs per week

- 1kg of vegetables per week

- 1kg of fruits per week

- 1kg of starchy roots per week

- 1 cup of coffee per day

This indirect water use totals 117kL per month. This is 10 times more than my direct water consumption and is largely "invisible" to me. The largest culprit is meat-eating, resulting in 54% of my water, followed by cereal products with 25%.

Both my direct and indirect water usage combined comes out to 129kL per month.

When it comes to addressing this 129kL per month, it's not about extracting more water for other people who don't have access to water. Humans are already quite capable of water extraction -- the problem is in sustainable water extraction. Instead, we should ensure that the world's natural infrastructure remains operational to produce freshwater. Examples of natural infrastructure are our rivers, lakes, and wetlands.

Living in Sydney, the water I produce is first processed through treatment plants before being discharged into the ocean. This helps ensure that the waterways stay clean. Unfortunately, not all countries are as lucky as Sydney, and some discharge polluted water directly into the ocean.

The water I consume directly, however, comes primarily from the Warragamba Dam, which mostly acts as a reservoir, instead of a hydroelectric dam. Dams have large issues with damaging natural systems, and it would do a large amount of good to replace dams worldwide, or let dams release pulses of water. However, initiatives that target dams and rivers are few and difficult to pin down evidence of efficiency.

Most of my water consumption is indirect and is captured through agricultural practices. Australian agriculture is affected by mismanagement of the Murray-Darling basin, where a catchment larger than Egypt has been slowly deteriorating. Wrapped up in political events, the bottom line shows that despite efforts, the rivers are dying and up to a million fish are dead. Yet again, it is hard to find any targeted initiative that has evidence of efficiency.

The remaining infrastructure to consider is wetlands. Wetlands serve many functions, only one of which is water purification. An arbitrarily discovered EPA study suggests one particular wetland processes 378.5kL per day for a 1.3ha site. This provides a ballpark figure of processing 291kL per day per hectare. Therefore, I would need to support 1 hectare of wetlands for 6 days to cover my yearly water usage of 1548kL.

Wetlands are protected globally through the Ramsar Convention. Ramsar identifies wetlands of importance, and participating countries ban harmful industry actions in the area and conservation groups are set up to protect and monitor it. One particularly large Ramsar site nearby is the Hunter Estuary Wetlands. It meets 3 out of the 9 Ramsar criteria.

The Hunter estuary wetlands have a total area of 3,388ha and incurs yearly expenses (2013) of 320,000AUD. Given that they are financially struggling, it suggests that they have cut costs since and also that the marginal utility gain from additional donations would be higher. However, with this area and yearly expense, it suggests it costs on average 94AUD to maintain each hectare for a year.

Given that I only need to maintain a hectare for 6 days to process my volume of water, it only costs me 1.6AUD per year. Of course, this is an extremely crude calculation with numerous assumptions (e.g. same water processing rate as EPA benchmark, or than the full area of wetlands is protected or functioning equally, or that there is a linear relationship with business expenses and wetland function). As a result, I'd be happy to be wrong by a factor of 100, and decide that I should dedicate 160AUD per year, or 108USD.

Result: ~9USD per month

Biodiversity and loss of ecosystems

It is difficult to determine exactly how much biodiversity is lost per person. Clearly, the footprint of my house excludes all wildlife but the urban flora and fauna. However, there are many indirect losses, such as from the farmland required to produce our food.

An easier approach is to look at our total ecological footprint. Earlier in this article, I stated that the average Australian had 6.6 global hectares of infrastructure per capita. This is one of the highest in the world. If we loosely approximate these to be regular hectares, I would need to somehow protect at least 6.6 hectares of ecosystem out there.

These hectares of ecosystems aren't just limited to Australian ecology. Thanks to global trade, they cross many typologies, such as forests, grasslands, deserts, mountains, and marine environments. As such, I turned to the WWF, which has initiatives targeting many parts of the world.

The WWF seems to dedicate a large portion of its funds to program expenses, despite a 750,000USD salary for its CEO. Its latest yearly expenses were 247 million dollars. But what exactly did it achieve with such spending?

To answer this, I turned to the WWF habitats page, which talks about their initiatives in different ecosystems. Although independent analysis rather than claims from the WWF itself would be preferred, it's a starting point.

On the page on wetlands, they make this claim:

About 75% of the sites added to the [Ramsar] list since 1999 were included as a result of WWF’s work.

Downloading the Ramsar database allows us to filter sites added in the 2000 or later, of which there are 1,359 sites. 75% of this is 1019 sites. If we sort it in terms of site area and take the middle 1,019 sites, we estimate that the WWF has protected a total of 17,546,560ha of wetland. This is about 10% of the total added area of all sites (176,141,282ha), so clearly there are some large outliers in the top 12.5%, which suggests that this number is an underestimate.

For marine environments, the Marine Protected Areas is the equivalent of the Ramsar sites. Its main proponent is the Marine Conservation Institute, but WWF does play a role and has helped add MPAs to the map since the inception near the year 2000. However, I have not been able to find such a bold claim similar to the Ramsar statement of adding 75% of new sites.

The MPA aims to cover 30% of the ocean, but currently only covers 4.8%. However, the ocean is mindbogglingly large, with an area of 36,100,000,000ha, so this 4.8% comes out to about 1,732,800,000ha. Conservatively if WWF's contribution was 1% of this area, the WWF protects 17,328,000ha.

For forests, WWF started the ARPA project in 2002. It is the world's largest conservation project targeting the Brazilian Amazon region. By 2017, it has protected 58,274,784ha. Admittedly, it was also thanks to the help of other organisations, even if WWF did start the initiative and make large contributions. There were four main contributors: the Government of Brazil, WWF, the Linden Trust for Conservation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, but let's say the WWF contributed merely 10%, meaning that the WWF had protected 5,827,478ha.

Just through these three large initiatives alone, over 19 years (with each year spending 247 million dollars), the WWF has a cost effectiveness of 115USD per hectare protected per year. For the average Australian ecological footprint of 6.6ha (loosely approximated from global hectares), it costs just 64USD per month to offset my loss in biodiversity.

Given that there are other unaccounted initiatives that target the polar regions, desertification, mountains, grasslands, and indirect protection that surely exists from WWF's work, it would be a reasonable conclusion to say that a monthly 64USD (90AUD) is enough to both offset and be net-positive.

Result: ~64USD per month

Waste management

The issue with waste is that they are usually ecological dead ends. Waste that isn't composted, or recycled turns into landfill that very little new life can spring from.

Measuring my direct waste was easy. I weighed my unrecycled trash every time I threw it out. I end up throwing out about 52kg of waste per year. Clearly, I run a very lean lifestyle compared to the average per capita municipal waste of 560kg. However, it is very hard to measure my indirect waste, especially as the waste industry can be quite opaque. The Bureau of Statistics suggests Australians produce 2,215kg of waste per capita per year.

The solution to the waste problem, apart from consuming less, is to change our manufacturing methods to consider the entire lifecycle of the product. There is a concept known as Cradle-to-Cradle, where products are designed to be waste free, as part of a natural cycle of nutrients. If humans produced products this way, our waste wouldn't be waste.

The Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute was started by the creators of the cradle to cradle movement, and offer product certification and resources to allow manufacturers to change their ways.

This is a relatively new initiative, but they do make some claims on their donation page, such as:

Shaw Industries makes 80% of its 4.5 Billion in sales with Cradle to Cradle Certified™ products. Aveda was the first beauty company to manufacture its products with 100% wind power in its manufacturing facility in Minnesota. IceStone has moved, since 2003, 10 million pounds of glass out of the waste stream as part of their product design and manufacturing.

Let's consider the first claim, as Shaw Industries is one of the largest carpet manufacturers out there. Shaw Industries has an incredible sustainability track record, and have produced Cradle to Cradle products since 2010, which is when the Cradle to Cradle Institute started. In 2010, ~50% of their sales were in Cradle to Cradle products, and in 2019, they are at ~90%. This increase of 40% of sales across 9 years represents ~10 billion dollars in sales. If the average sale of a product was at a pricey 100USD per square metre and each square metre weighed ~2kg, this equates to 202,400,000kg of Cradle to Cradle products. If the average yearly expenses of the institute are 2,312,135USD, this results in a cost effectiveness of 10 cents per kilogram.

To cover the average Australian waste of 2,215kg, it results in 221USD per year, or 19USD per month. This is likely enough to be net-positive, as we have assumed that no waste is already diverted from landfill, and only considered one of the claims - they have certainly made strides elsewhere.

Result: ~19USD per month

Air pollution and quality

Air pollution is a tricky one. Although Sydney's air quality is 20% below the safe level of PM2.5 annual exposure (i.e. it's very clean), the atmosphere is the dumping ground for a lot of waste so it is hard to attribute air pollution to a particular person. If we merely took that figure at face value, it would suggest that Australia is already "net-positive" in terms of air quality (at least when compared to the WHO baseline). It is also hard to find initiatives that have published measurable results in reducing air pollution.

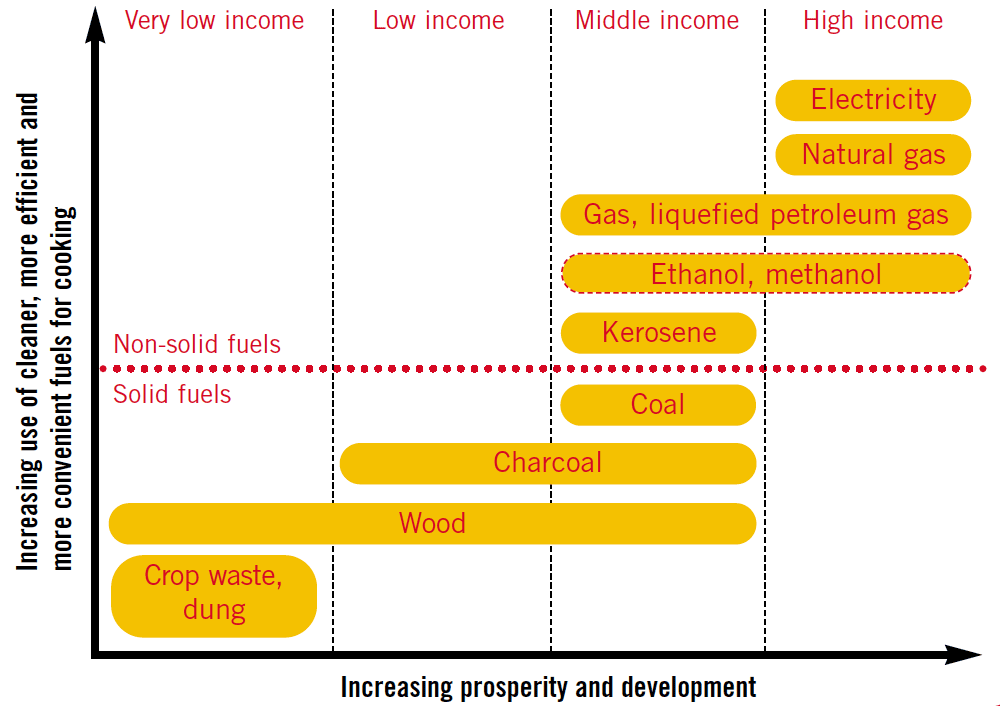

Air pollution is primarily due to fuel burning. Initiatives that help most would be to do with switching to greener fuel sources: for our power stations, transport, and cooking. In fact, EnergyAustralia offers 100% green energy for no cost to consumers. So switching to that would be extremely cost effective: as it would cost nothing!

The type of fuel that is burned has a strong correlation with income, as studied by the WHO. Poor people have to rely on unhealthy fuel sources which create health problems. The WHO estimates 3 billion people who have to burn wood, dung, and coal inside their homes. The more we can raise people out of poverty, the sooner they can naturally make the switch to better infrastructure. As an example, the WHO states that the pollution in a hut with open fire is 100 times more than the Berlin city centre. The switch between solid fuel and gas or kerosene improves air quality by 10 times. A little less optimistically, the purchase of an improved stove design still results in a decrease in pollution from 50 to 90%. This gives an idea of the magnitude of cost effectiveness in targeting the global poor.

The good news is that tackling global poverty is a well-researched area with plenty of cost effective choices. With our remaining budget of 22 per month, we can donate to GiveDirectly, where you can, well ... simply give that money to the extreme poor. This is almost equivalent to 1 year of their universal basic income initiative (0.75$ per day - compared to the global poverty line of 1.25$ per day), where they can rebuild their lives. The results show that they spend this on assets and nutrition primarily, with a resultant increase in earning, lifting them out of the global poor.

If you wanted to explore other more directly related initiatives to explore would be those such as CityTrees, the Clean Air Task Force, the World Health Organisation, the Coalition for Clean Air, or one of many Smokeless cooking initiatives that swap out cooking equipment in poor countries.

Without any other stronger quantitative foundation, in addition to my own switch to 100% green energy, I have chosen to target the global poor, rather than more direct approaches. I would encourage readers to decide what approach suits them best and to do their own research.

Result: ~22USD per month

A budget for a net-positive life

Our final monthly budget is as follows:

- 14USD donated to Cool Earth

- 7USD donated to the Albert Schweitzer Foundation

- 9USD donated to the Hunter Estuary Wetlands

- 64USD donated to the WWF

- 19USD donated to the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute

- 22USD donated to GiveDirectly

This totals 135USD per month, or 1,620USD per year, which is 5% of a 32,400USD yearly income. It covers a large range of issues, chosen to reflect the various dimensions of our non-anthropocentric production and consumption as a species.

The budget demonstrates that with a small donation it is possible to actually make a large and measurable impact as an individual. These calculations have been extremely conservative on purpose, and I have refused to double count benefits (e.g. work by the WWF would also have impacts on the carbon footprint, but I did not count it twice). I should warn, however, that I am not a subject matter expert, and so if you are more experienced in any of the fields I have mentioned in this article and can help suggest improvements, please send me an email!

Net-positive living is just the beginning! There are so many other important issues to consider in the world, and if you make more than 32,400USD (pre-tax) per year, perhaps you can donate even more than the small budget I set in this article. Please feel free to explore Giving What We Can, GiveWell, and 80,000 hours.

As a final note, I should emphasize that in this article, I have only focused on the financial. Financial ballparks are not the only approach nor guaranteed to be the best approach to the world's problems. In fact, there are many ways where cost-effective estimates are misleading. Personally, I believe that ethical offsetting is not enough, and it is absolutely vital to also change our behaviours - to recycle when possible, to choose renewable sources, and to reduce our materialism. Everybody will have their own unique and valuable contributions to the world, so I urge all readers to research, evaluate, and do the best you can, in your own way.

We can change things.